David the Dreamer is a bizarre and beautiful book, published in 1922 and never reprinted. Ten surreal chapters recount ten different dreams, with titles like these:

“How David Went to Do an Errand at the Grocery and Walked Among the Snow-capped Mountains”

How David Got Lost at Sea in the Goldfish Bowl”

“How Jim the Rabbit Sailed a Boat and David Met Father and Mother When They Were Children”

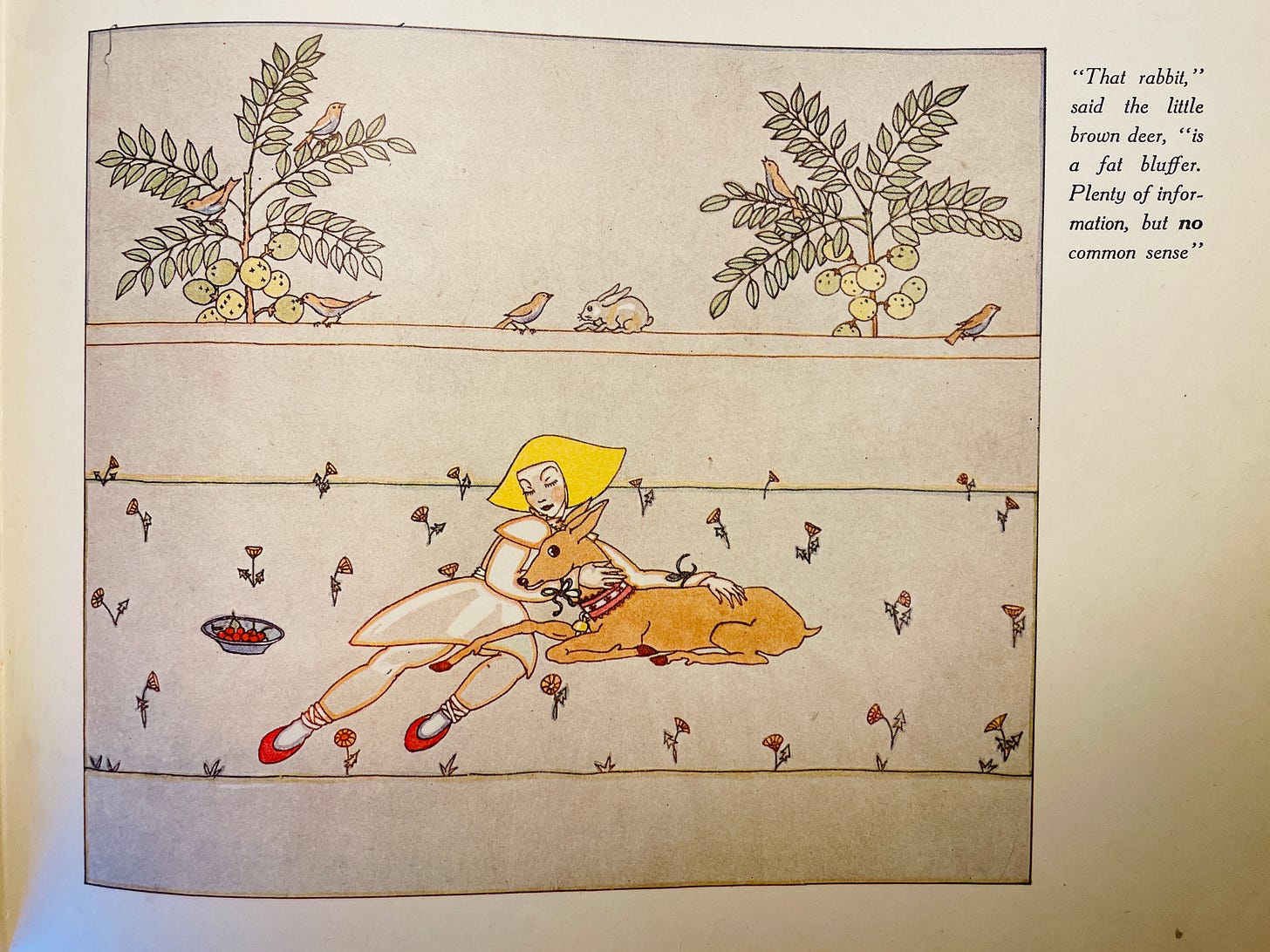

It’s lavishly produced, nearly 12 inches long (24” when open!) with lovely endpapers and stunning illustrations:

The author, Ralph Bergengren, was a poet and essayist whose writing appeared frequently in The Atlantic. There, in a cranky 1906 polemic against Sunday comics, Bergengren laments a race to the bottom in reading material for children. According to him, it’s all slapstick violence and stereotypes, shock and schlock, with equally crude illustrations.

“The cry of the publisher,” complains Bergengren, “is for ‘fun’ that no intellect in all his heterogeneous public shall be too dull to appreciate.”

David the Dreamer is precisely the opposite of those comics Bergengren hated. The stories are slow and strange, serving almost as a frame upon which to stretch the delicate drawings of an androgynous protagonist making his way through dreamscapes.

The book is quite magical in itself, but it takes on a completely different meaning when you learn who created these dreamscapes:

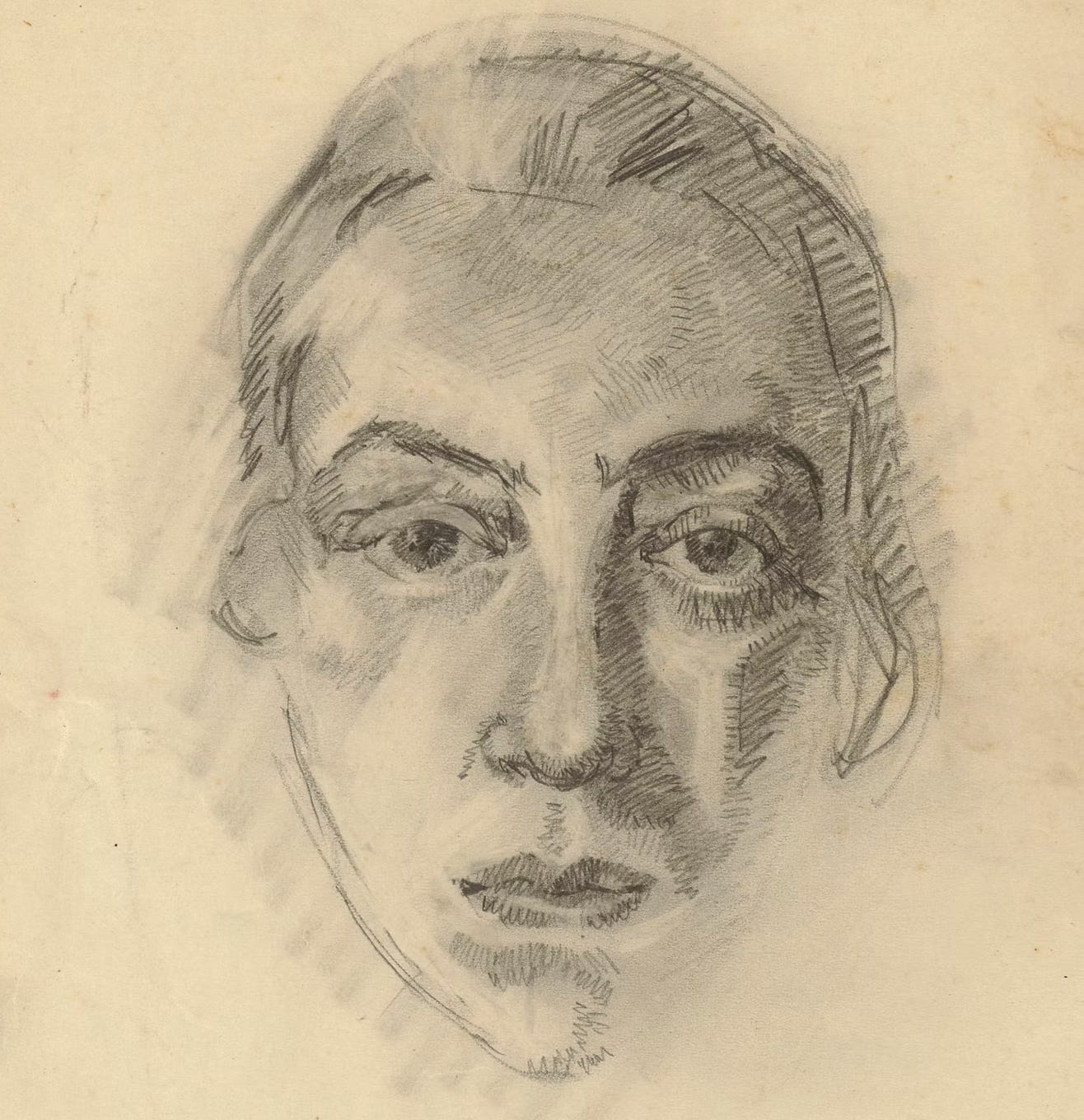

In 1892, Tom Seidmann-Freud was born Marta Freud, the daughter of Sigmund Freud’s sister, in Austria. At 15, she changed her first name to Tom, apparently to avoid sexism in the art world. (Some claim she wore men’s clothes throughout her life, her grandson denies it.) There are, as far as I can tell, almost no photos of her as an adult, but her family website preserves this self-portrait:

After attending art school in Berlin, Tom hung out with Jewish intellectuals and literati, smoked endless cigarettes, and, at 28 years old, fell in love and married a journalist named Jacob “Yankel” Seidmann. Two years later she gave birth to their daughter — the same year David the Dreamer was published.

That’s when the dreams ended and the nightmares began. Tom and her husband started an ill-fated publishing venture that eventually bankrupted them. In 1929, Tom discovered Yankel hanging from a rafter in her home, and herself descended into the depths of despair. Sigmund Freud’s own counsel could not save her, and at 38 years old she overdosed on sleeping pills.

It was while her business and family slowly collapsed that Tom Seidmann-Freud produced a series of children’s books widely acknowledged to be masterpieces of book design. Many of them are extremely rare, rarer than most children’s books, because of another nightmare: The Nazis burned whatever they could get their hands on. They also burned Seidmann-Freud’s mother, who ended up in a concentration camp.

Angela, her daughter, was adopted by her sister and managed to escape the Holocaust. Like her mother, changed her name: She choose Aviva, Hebrew for “spring.”

Rereading David the Dreamer in light of this biography was a completely different experience. Too often, as a father, I barely listen to my young daughter when she tells me about her dreams. They are disjointed, surreal, childish.

But in Seidmann-Freud’s illustrations I was reminded of why children’s dreams are so special. Children live in a world that is simultaneously constrained and free — a world narrowed by their lack of experience, but free from the nightmares of adult problems, bankers demanding repayment of loans, soldiers goose-stepping outside, despondent family members. And even when those problems force themselves upon children, they are seen differently, refracted through innocence into simpler shapes and colors.

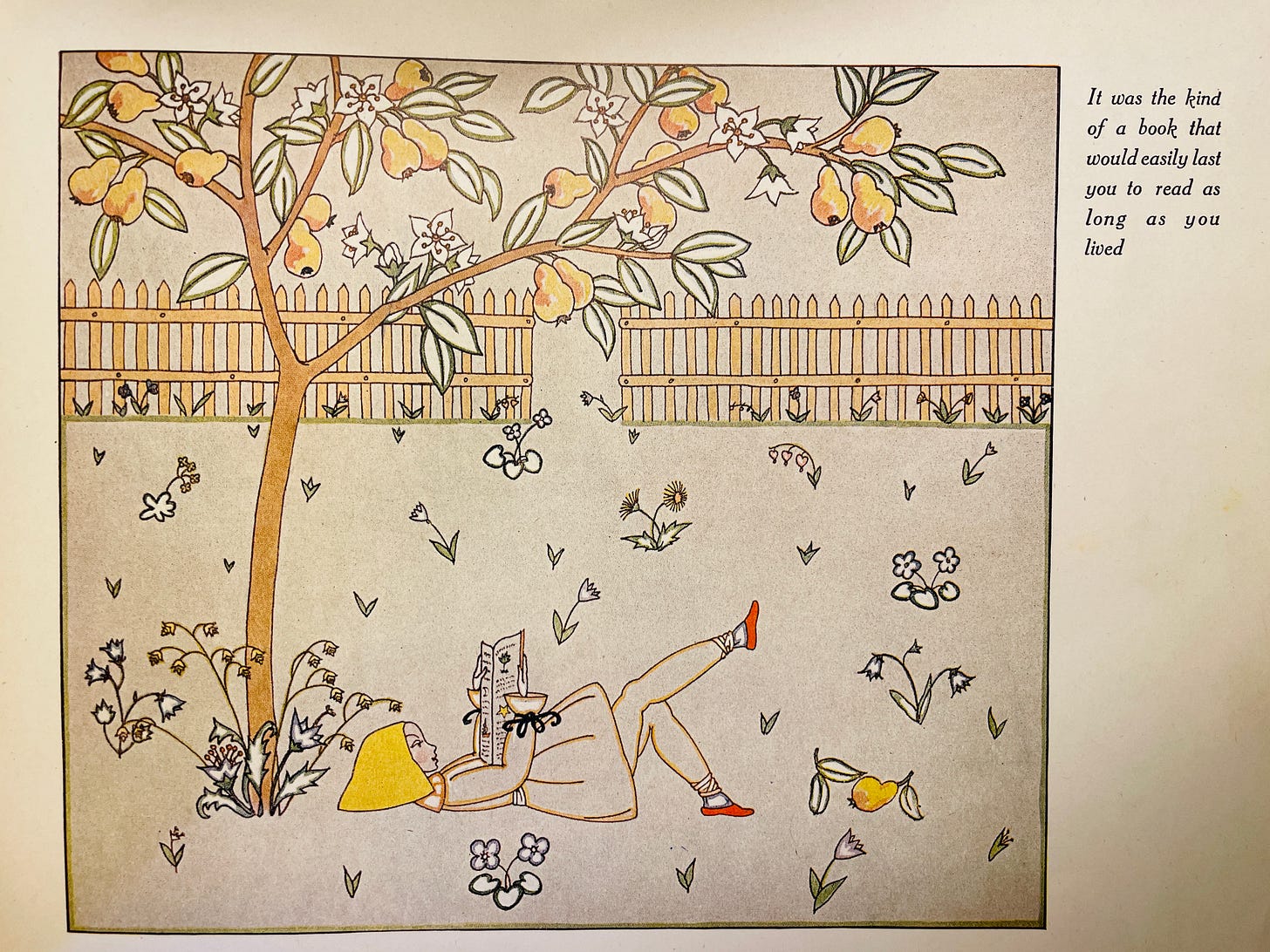

In my favorite chapter of the David the Dreamer, we read about “how a book read David.” In it, David discovers a magical book. The content of the book is constantly changing, “so that it was the kind of a book that would easily last you to read as long as you lived.”

In reality, this magic does not require the contents of a book to change. All it requires is change in the reader.

When I first read David the Dreamer, I read it as an unusual children’s book with fantastic illustrations. When I reread it, after learning about Seidmann-Freud’s life, it became something else entirely.

May you all find books that last you as long as you live! Thanks for coming along on this installment of Book Glory, and I’ll see you for the next one.

(Paid subscribers can keep reading to find out where and how to obtain Seidmann-Freud’s books, which are exceptionally difficult to find.)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Glory to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.